Despite the pain of missing my family, I've been surprised how much healing and happiness I've experienced through writing my life story for my kids.

As we have interviewed clients during the pandemic, often by video-conference, we have found ourselves called on not only to record memoirs, but to provide grief support, conflict mediation, and other conversations typically reserved for therapists. While we’re quick to assure clients we are not credentialed counselors, researchers have concluded that the mental health benefits of reminiscence and writing your life story are too strong to ignore. (jump to the sources below).

Life Story Work holds therapeutic benefits

For several decades, Life Story Work, or LSW, has increasingly appeared in geriatric nursing manuals and medical journals (Wills & Day, 2008), but this was not always the case. As recently as the 1960’s, “reminiscence” was considered an early sign of senility and mental decline. Your grandparents might love to spin a story, but don’t let them get carried away. . . or so the thinking went. One of the first to argue otherwise was Dr. Robert Butler, founder of the New York-based International Longevity Center, who in 1963 contended that a “Life Review” was an important part of healthy aging (Butler, 1963).

In the decades since Dr. Butler’s first work, numerous studies have confirmed the psychological and social benefits of everything from conversational reminiscence to clinical Life-Review Therapy. It is now widely accepted that recalling and retelling our life experiences has positive impact on many mental health indicators, from depression, to cognitive function, to trauma recovery, and general well-being (Westerhof & Slatman, 2019).

Among the wide-ranging benefits of reminiscence, the most significant benefit observed in trials is the alleviation of symptoms of depression, anxiety, and trauma. Though the results vary with different approaches, in some instances the benefits of Life Review have been shown to be comparable to cognitive-behavioral therapy (Pinquart & Forstmeier, 2012) and a viable alternative to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy (Bohlmeijer, Smit & Cuijpers, 2003). Anyone who has enjoyed the catharsis of a good conversation with friends might expect this to be true, and controlled studies bear this out. A 2012 meta-analysis published in Aging and Mental Health reviewed dozens of trials from across the globe and found significant improvement in depression symptoms (Pinquart & Forstmeier, 2012). The results were similar even when comparing diverse participant groups across a variety of techniques and approaches. The findings were especially promising among those in retirement communities, where loss of hope, identity, and meaning are well-documented troubles (Claudia, Igarashi, Yu & Chin, 2018). The results among those suffering from chronic physical illnesses such as cancer and AIDS were also noteworthy (Pinquart & Forstmeier, 2012).

Reminiscence, whether in conversation or in writing, has been shown to improve general well-being, ego-integrity, sense purpose in life, cognitive performance, social integration, and death preparation.

Not all Life Story Work is created equal

While everyone enjoys casual reminiscing with friends, left to our own, storytelling can have detrimental effects. Those who have gossiped around the ‘bridge’ table or nursed old gripes over a dram of Scotch know the power of stoking anger and conflicts from our past. For that reason, clinical practitioners favor structured approaches to Life Story Work. Unlike simple life storytelling, a systematic “Life Review” seeks to process all major life events and turning points, seeking coherence and resolution. That’s not to say grief or anger or conflict are avoided. To the contrary, a Life Review includes both successes and failures, joys, hardships and tragedies. When clinical best practices are followed, the emphasis is not on commiseration, but evaluating the significance of the past, resolving conflict, and understanding the themes of our lives. Whether you’re 65 or 95, researchers have concluded that reviewing our lives with a professional counselor, social worker, or trained Life Storyteller is good for our health (Bohlmeijer, Roemer, Cuijpers & Smit, 2007).Long-term care providers are taking note

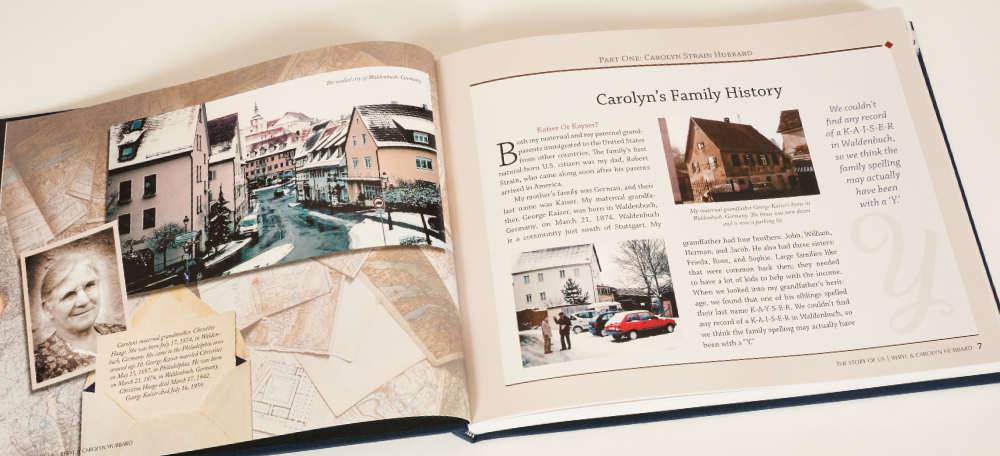

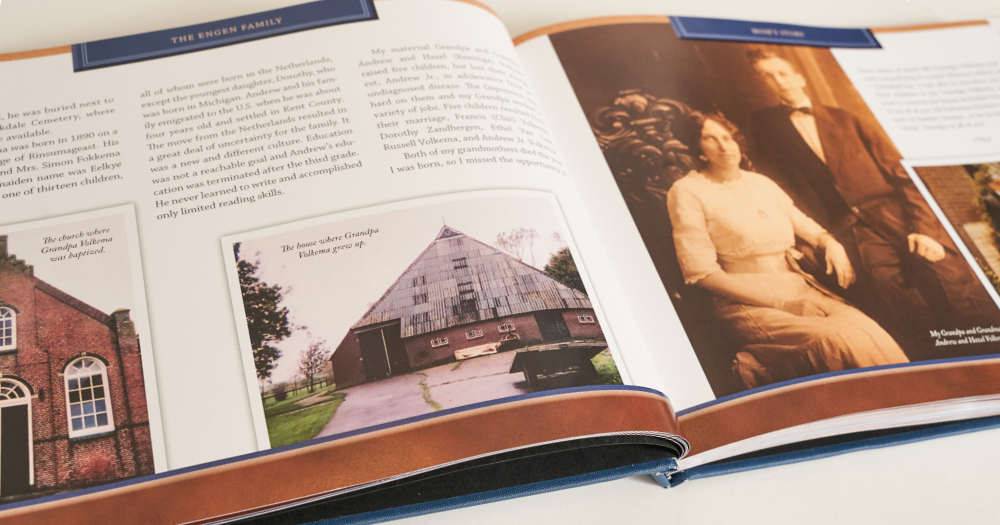

Today, as reminiscence has become mainstream therapeutic practice, retirement and nursing care providers are recognizing the potential of forms of Life Storytelling for improving their quality of care (McKeown, Clarke & Repper, 2006). Increasingly, as practitioners discover the value of understanding patient’s attitudes and perspectives, Life Story Work is gaining recognition as an essential for “person-centered care” (Wills & Day, 2008) Though conversational approaches yield some benefit, numerous researchers have highlighted the value of Life Story Books in their work. An “LSB”, or personal history, or memoir as they are variously described, can solidify a sense of personal identity in old age, giving long-term care practitioners a more holistic view of residents by understanding their unique personal and family history (Hewitt, 2013). The result is more personalized assessment of patients (Anderson, Hobson & Steiner, 1992) and greater possibilities for individualized care (Hansebo & Kihlgren, 2000). Though the Covid pandemic continues to keep us separated and sequestered, Life Story Work need not be limited by quarantine protocols. Thanks to everyone’s growing familiarity with video-conference technology, Life Storytellers are able to offer virtual services to more people than ever before. As a publisher of Life Story Book and memoirs, we have had the privilege of helping dozens of clients begin a Life Story project during the Covid Pandemic. We have helped others give a Life Story Book gift for parents or grandparents. In many ways, the limited social options and quarantines make this the perfect time to gather photos and memorabilia, family biography and personal memoirs, ancestry and genealogical research, as a gift for future generations. Our aging loved ones may be enduring the loneliness of increased physical isolation, but their memories, perspectives, and insights need not be kept to themselves.

Though the Covid pandemic continues to keep us separated and sequestered, Life Story Work need not be limited by quarantine protocols. Thanks to everyone’s growing familiarity with video-conference technology, Life Storytellers are able to offer virtual services to more people than ever before. As a publisher of Life Story Book and memoirs, we have had the privilege of helping dozens of clients begin a Life Story project during the Covid Pandemic. We have helped others give a Life Story Book gift for parents or grandparents. In many ways, the limited social options and quarantines make this the perfect time to gather photos and memorabilia, family biography and personal memoirs, ancestry and genealogical research, as a gift for future generations. Our aging loved ones may be enduring the loneliness of increased physical isolation, but their memories, perspectives, and insights need not be kept to themselves.

Sources

- Wills, T., & Day, M. R. (2008). Valuing the person’s story: use of life story books in a continuing care setting. Clinical interventions in aging, 3(3), 547–552. DOI: 10.2147/cia.s1620

- Butler, R.N. (1963). The Life Review: An Interpretation of Reminiscence in the Aged. Psychiatry, 26(1), 65-76. DOI: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

- Westerhof, G.J. & Slatman, S. (2019). In search of the best evidence for life review therapy to reduce depressive symptoms in older adults: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology, 26(4). DOI: 10.1111/cpsp.12301

- Pinquart, M., & Forstmeier, S. (2012). Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: A meta‐analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 541–558. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2011.651434

- Bohlmeijer, E., Smit, F., & Cuijpers, P. (2003). Effects of reminiscence and life review on late‐life depression: A meta‐analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(12), 1088–1094. DOI: 10.1002/gps.1018

- Lai, Igarashi, Yu & Chin. Does life story work improve psychosocial well-being for older adults in the community? A quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatrics (2018) 18:119. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-018-0797-0

- Pittiglio, Laura. (2000). Use of Reminiscence Therapy in Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Lippincott’s Case Management. 5.5, 216-20. DOI: 10.1097/00129234-200011000-00002

- Watt L.M & Cappeliez, P. (1995). Reminiscence intervention for the treatment of depression in older adults. In: B.K. Haight & J.D. Webster (eds.), The art and science of reminiscing: theory, research, methods, and applications (pp. 221-232). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

- Butler, Robert N. (1974). Successful Aging and the Role of the Life Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 22(12), 529-535. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1974.tb04823.x

- Parker, R. G. (1999). Reminiscence as continuity: Comparison of young and older adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5(2), 147–157. DOI: 10.1023/A:1022931111622

- Wong, P. T. P. (1995). A stage model of coping with frustrative stress. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspectives on motivated activities, 339-378. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, Smit F. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 11(3), 291-300. DOI: 10.1080/13607860600963547

- McKeown J., Clarke A., Repper J. Life story work in health and social care: systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(2), 237-47. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03897.x

- Wills, T., & Day, M. R. (2008). Valuing the person’s story: use of life story books in a continuing care setting. Clinical interventions in aging, 3(3), 547–552. DOI: 10.2147/cia.s1620

- Hewitt H. A life story approach for people with profound learning disability. British Journal of Nursing. 9, 90-95. DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2000.9.2.6398

- Anderson KH, Hobson A, Steiner P, et al. Patients with dementia: Involving families to maximise nursing care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 1992, 18, 19–25. DOI: 10.3928/0098-9134-19920701-07

- Hansebo G, Kihlgren M. Patient life stories and current situation as told by carers in nursing home wards. Clinical Nursing Research. 2000, 9, 260–79. DOI: 10.1177/10547730022158582