FALLEN SOLDIERS DIE AT HOME

An Essay by Beverly VandenBosch Eckhoff, Published May 26, 2002 in The Grand Rapids Press

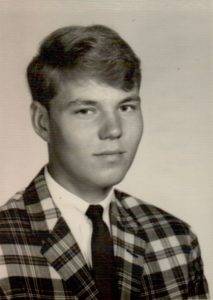

One evening in February 2001, my husband and I, along with my five siblings and their spouses, gathered to examine the contents of some boxes from our parents’ home. The cartons contained medals, letters, and miscellaneous mementos of our brother, Dwaine VandenBosch, who was killed in Vietnam on March 10, 1968. We began scrutinizing a few papers and, finding it simply too painful to do as a group, agreed to go through prized materials individually.

One evening in February 2001, my husband and I, along with my five siblings and their spouses, gathered to examine the contents of some boxes from our parents’ home. The cartons contained medals, letters, and miscellaneous mementos of our brother, Dwaine VandenBosch, who was killed in Vietnam on March 10, 1968. We began scrutinizing a few papers and, finding it simply too painful to do as a group, agreed to go through prized materials individually.

My brother was seven years my junior when he died at 20. It changed my life and that of my family forever.

One Month in Vietnam

Pfc. Dwaine VandenBosch left Grand Rapids on February 10, 1968, to serve with the 25th Infantry Division in Vietnam. He received one week of training there before joining the “Wolf Pack,” a reconnaissance platoon. He was fighting during the Tet Offensive and wrote that he would probably make rank quickly because when new men would come in, he would be over them.

I read these letters for the first time when I went through the boxes. I understood then, of course, that when new men came in, they were to replace others who were injured or did not survive the battle. I also learned that Dwaine’s platoon was supposed to have 30 men. When he joined them, there were 13. The four backup companies were shorthanded by almost half as well.

Was he sent to certain death? It would seem so. Today, his name is engraved on a wall in Washington, D.C., along with the names of nearly 60,000 other military personnel who lost their lives in that war. (Dwaine is listed Panel 44E, Row 8.)

One month after he departed for Vietnam, on March 10, 1968, my parents received a telegram reporting that Dwaine was missing in action. We didn’t speak of the imagined horrors and dreaded possibilities as we waited, aching to hear something definite. On March 15, we received another telegram confirming his death. Dwaine was the only one of his unit killed when his base came under hostile mortar attack on March 10. For several more days, we waited for his body to be returned to the states, and on March 25, 1968, we laid him to rest in Rest Lawn Cemetery, the 57th Kent County Man to die for his country (in the Vietnam War).

A Void in the Family

Our family of seven children ranging in ages from 28 to 12 was now reduced by one. Two of us were married, and in addition to his parents, two brothers, four sisters, and his fiancé, Dwaine left two nieces and nephews. It is difficult to explain death to a 5 and 6 year old son and daughter, but how does one begin to explain why men would kill their uncle in particular? Why indeed!

We spent hours visiting with Dwaine’s body escort, who came to our home and shared what he could about the war and Vietnam. Later, we passed exhausting hours at the funeral home, greeting long lines of people who shared our grief.

We are a family of faith. Though we miss our brother every day, our loss has taught us the importance of making each day count, because life is brief, and when we die, we leave only the memory of how, and for who we lived. Additionally, we know the value God places on each life. He made us, and our life is His to take at the appointed time. We know that Dwaine lives in heaven, and we know the peace of God. How does one endure such an experience without these assurances?

While our faith gives us a sure hope of being with him again, it does not mean that we failed to go through the process of denial, anger, and grief that accompany death in this life, particularly that of a close family member.

Dwaine’s death left an immense void in our family, and anger and grief brought changes in Dad that were difficult to observe. He had never supported our country’s involvement in Vietnam. For a long time afterward, Dad wasn’t himself, and in the months immediately following, he spent hours at the cemetery alone, using whatever excuse he could find to be there. He seemed unable to deal with his anger and grief. We lived daily with Dad’s special pain that added to that of our own. We were all casualties of that terrible war.

‘Sad Time’ Comes Around Every Year

Many years later, Dad began to come to terms with the death of his son, and though his grief never died, life went on. After Dad passed away, I took his calendar from the kitchen wall. On the date March 10, 1999, 31 years after Dwaine’s death, he had penciled in, “Sad Time.”

We each deal with death in our own way. Our family talked about Dwaine often, keeping his memory alive for the extended family that came along in the years that followed. Nonetheless, other than his clothing and photos, most of the tangible reminders were packed away in boxes. Until recently, I was unaware of the letters Dad had written to officers and my brother’s fellow servicemen or the replies from some of them.

Memorial Day has a Special Meaning for the Families

Soon, we will celebrate Memorial Day. As many prepare for camping trips, picnics, parades, and community memorial services, I pause to remember my brother, and to acknowledge the terrible loss others have experienced—others who have made a similar sacrifice for freedom, though they never fought in battle; others who still have open wounds, and who live in unending pain. I write for moms and dads, the sisters and brothers, and the extended family members whose every Memorial Day or family celebration is a day that reminds them of that family member who gave the supreme sacrifice for his country.

I write for those who, even today, stand at the airport and watch as the plane soars away, wondering what the future holds for their loved one on board. I write for those who saw their sons go off to fight a war that they believe should never have been fought, sent there by those whose sons would not go, and in the place of those whose courage failed them.

I write for those who, called on by God to respect those who rule over them, find it difficult because of “leaders” who themselves were unwilling to support their country.

Visiting war memorial in Washington, D.C., will impress anyone with the great price of freedom. I write for those who are still praying.

To quote Wendell Berry in his novel “Jayber Crow”:

“I imagined that soldiers who are killed in was just disappear from the places where they are killed. Their deaths may be remembered by the comrades who saw them die, if the comrades live to remember. Their deaths will not be remembered where they happened. They will not be remembered in the halls of government. Where do dead soldiers die who are killed in battle? They die at home—in…thousands and thousands of houses…where the news comes, and everything on the tables and shelves is all of sudden a relic and a reminder forever.”

For us and all families who bear such a loss, our grief remains, folded and stored away like the flag presented at the cemetery. We mourn for the family whom we will never know and the happy times that might have been. We cling to the medals presented and letters received, and gaze at the photos of the young man in uniform who will always be 20 years old. We go on living. And remembering.